A study out of the School of Management and Business at King’s College London has proven something that, anecdatally, also makes a lot of sense — that conscientious, above-and-beyond-type employees, who are successful at their jobs because of this drive, also experience significant emotional exhaustion, and struggle to keep a work-life balance.

Participants in the study, all workers in a UK bank’s inbound call-centre, reported feelings of being drained and “used up.” This was often because of workplace policies, that, in today’s age of tenuous employment with vaguely defined boundaries, called on participants to go beyond their job descriptions.

While participants were frequently rewarded for their “organizational citizenship behaviour,” in the form of being considered for raises, job advancement, and being thought of as generally dependable, this goodwill had a dark side.

“Conscientious workers have been noted for their dependability, self-discipline and hard work, and their willingness to go beyond the minimum role requirements for the organization. They are also said to make a greater investment in both their work and family roles and to be motivated to exert considerable effort in both activities (not wanting to “let people down”), thus increasing work-family conflict and leaving them with little resource reserve. […]

Our study shows that a possible overfulfillment of organizational contributions can lead to emotional exhaustion and work-family conflict. […] Managers are prone to delegate more tasks and responsibilities to conscientious employees, and in the face of those delegated responsibilities conscientious employees are likely to try to maintain consistently high levels of output. […] The consequences, however, may be job-related stress and less time for family responsibilities.”

I do wonder if the fact that they drew from a pool of employees in an already emotional-labour heavy industry made the study’s results even starker. It will be interesting to see if further research into other types of work, as the study’s conclusion calls for, might uncover the same trends. I know that in my working life, I myself have seen firsthand proof of the adage “If you want something done, ask a busy person.” This study shows that, similarly, “If you want something done well ask a conscientious person” — but maybe now we have a responsibility to think about the personal fallout of that request.

With the veritable explosion of technology and online platforms in recent decades, research is understandably catching up to the core truths about how our (comparatively un-evolved) brains and bodies interact with these almost parallel realities. One narrative has us at the mercy of insidious tech that erodes our willpower and enslaves us to our glowing blue screens. But new research involving twins and social media use is shedding light on a possible genetic component to our online habits — and, paradoxically, showing us how a lot of it can be modulated by choice.

The new study, authored by researchers at King’s College London, and published recently in the journal PLOS ONE analyzed online media use of 8500 teenage twins, both identical and fraternal. By comparing their behaviours and the amount of genes they shared (identical twins share all, and fraternal half), the researchers were able to determine how much of their online engagement was nature, and how much nurture. The (rather complicated!) equation is as follows:

“Heritability (A) is narrowly defined as the proportion of individual differences in a population that can be attributed to inherited DNA differences and is estimated by doubling the difference between [identical] and [fraternal] twin correlations. Environmental contribution to phenotypic variance is broadly defined as all non-inherited influences that are shared (C) and unique (E) to twins growing up in the same home. Shared environmental effects (C) are calculated by subtracting A from the [identical] twin correlation and contribute to similarities between siblings while non-shared environmental effects (E) are those experiences unique to members of a twin pair that do not contribute to twin similarity.”

The results found that a great deal of heritability was at play for all types of media consumption, including entertainment (37%); educational media (34%); gaming (39%); and social networking, particularly Facebook (24%). At the same time, environmental factors within families were the cause of two-thirds of the differences in siblings’ online habits. That indicates that while we are what our genes are, their in-world expression can be molded by free will. A heartening thought for a species buffeted by so much technological change!

|

We’re lucky enough to be surrounded by so much gee-whiz tech nowadays – from the Mars rover to tortilla Keurigs – that it’s easy to forget that the definition of technology includes some elegantly simple concepts. The lever, the wedge and the pulley have all changed the world far beyond what their uncomplicated structures might indicate possible. We have learned that in simplicity lies a wealth of usefulness – and an amazing new lab tool with world-changing potential is demonstrating this to us yet again.

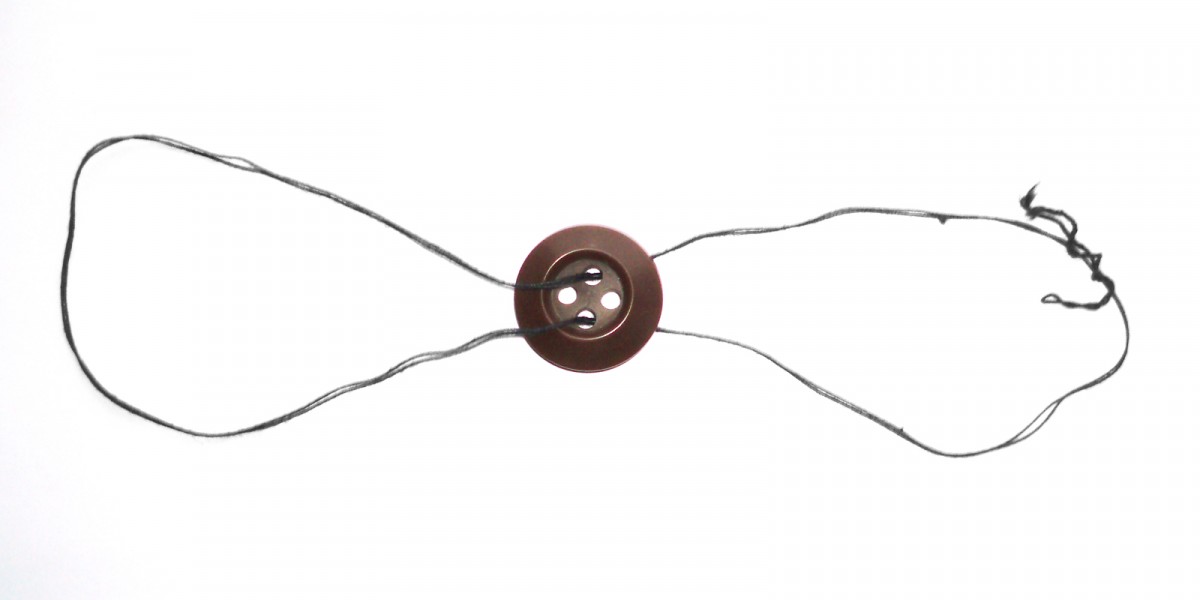

Stanford bioengineer Manu Prakash, of Foldscope and “frugal science” fame, and his team, have created an incredibly portable, outrageously inexpensive human-powered centrifuge, adapted from a popular and ancient toy design: the whirligig. A whirligig is essentially a paper disk or button, which, when suspended on a looped string that is pulled outward with the hands, spins quickly in the middle. Prakash’s “Paperfuge,” nearly identical in design, can spin hard enough to separate plasma from blood cells in 90 seconds. This allows important diagnostic procedures to be carried out quickly in clinics that may lack the electricity, funds, or infrastructure to obtain and use standard centrifuges. Faster diagnosis means faster help for patients in remote communities. The problem of a frugal centrifuge was longstanding: researchers had already tried adapting a salad spinner and an egg-beater into devices that were still too complicated to be effective and cheap. Then post-doc Saad Bhamla remembered a toy from his childhood that seemed suddenly promising: “They discovered that much of the toy’s power hinges on a phenomenon called supercoiling. When the string coils beyond a certain threshold, it starts to form another coil on top of itself. […] Physical prototypes came next. They tweaked the length of the string and the radius of the disc, and tried a variety of materials, from balsa wood to acrylics. In the end, though, the group settled on the same stuff Prakash used to build his Foldscopes . ‘It’s synthetic paper, the same thing many countries use in their currency,’ Prakash says. ‘It has polymer films on both front and back that make it waterproof, and it’s incredibly strong, as well.’” The Paperfuge removes critical barriers to access to diagnosis of many diseases, including malaria and HIV. In addition to the cool factor of a beloved childhood toy being repurposed for a higher calling, its existence will help prevent many deaths, and increase quality of life for huge segments of the world population. And that, I think, is the truest and best use of any technology. |

Curiosity may have killed the cat, but it might also breathe life into human workers’ careers — a different breed of curiosity, at least, that researchers are just starting to look at.

In a recent study done by the University of Oklahoma, Oregon State University, and Shaker Consulting Group, researchers have discovered the connection between “diversive curiosity” and flexibility in problem solving. Diversive curiosity is a trait that occurs in varying strengths in most people: those with stronger tendencies collect more and wider-ranging information in the early stages of approaching a problem, and exhibit greater plasticity in applying that information.

This type of curiosity is highly prized in the employees in today’s increasingly complicated workforce, as it directly results in a greater capacity for creative problem solving. On the other hand, “specific curiosity” — the kind that mitigates anxiety and fills particular, rigidly defined gaps in knowledge, is a trait that, in its strength in a subject, indicates a less-creative approach.

“[…R]esearchers asked 122 undergraduate college students, to take personality tests that measured their diversive and specific curiosity traits.

They then asked the students to complete an experimental task involving the development of a marketing plan for a retailer. Researchers evaluated the students’ early-stage and late-stage creative problem-solving processes, including the number of ideas generated. The students’ ideas were also evaluated based on their quality and originality.

The findings indicated that the participants’ diversive curiosity scores related strongly to their performance scores. Those with stronger diversive curiosity traits spent more time and developed more ideas in the early stages of the task. Stronger specific curiosity traits did not significantly relate to the participants’ idea generation and did not affect their creative performance.”

The researchers further discovered that lots of companies post job listings searching for candidates with creative problem solving skills, but often don’t end up hiring people who really have them. Now that the type of curiosity that correlates with those skills has been defined, personality tests can be used to identify the most successful candidates — leading to better “cast” employees, and happier humans and companies!

Throwing myself back into my standard working hours after a holiday period off has really made me think about how much we in the business world try to manage our sleep. We at DFC are able to set our own hours, but some hours are non-negotiable: my canine alarm clocks certainly don’t know the difference between four a.m. on a holiday and four a.m. on the day of an important client presentation. I do, and my quality of sleep is definitely different!

Because technology is advancing so quickly, we constantly find ourselves having to re-frame or re-approach ancient physical necessities like sleep. Over at The Atlantic, physician James Hamblin works through some of the big forces affecting sleep in our busy era. He comes uncovers some hard truths: some people are wired to excel on four hours of sleep, but most aren’t; and Red Bull can kill you!

But it’s not all doom and gloom. My favourite “hack” involves s deceptively simple action – putting your phone away at least an hour before bed. The sleep-killing effects of late-night screen time are well known, but Hamblin breaks down the brain science particularly vividly:

“When light enters your eye, it hits your retina, which relays signals directly to the core of your brain, the hypothalamus […] the interface between the electricity of the nervous system and the hormones of the endocrine system. It takes sensory information and directs the body’s responses, so that the body can stay alive.

Among other roles in maintaining bodily homeostasis—appetite, thirst, heart rate, etc.—the hypothalamus controls sleep cycles. It doesn’t bother consulting with the cerebral cortex, so you are not conscious of this. But when your retinas start taking in less light, your hypothalamus assumes it’s time to sleep. So it wakes up its neighbor the pineal gland and says, ‘Hey, make some melatonin and shoot it into the blood.’ And the pineal gland says, ‘Yes, okay,’ and it makes the hormone melatonin and shoots it into the blood, and you become sleepy. In the morning, the hypothalamus senses light and tells the pineal gland to stop its work, which it does.”

I’ve now taken to leaving my phone charging in another room as I sleep, and going back to a regular old alarm clock (remember those?) — for my bedside table, so I don’t blast my hypothalamus with blue light as I check the time. At the moment, I don’t feel the need to experiment with caffeine or melatonin, or any of the other interventions Hamblin describes. But you may — give the article a read and let us know what you think! Meanwhile, I will try reading it to Jill and Samson, to see if they will finally, finally understand what they are doing to me.

If you spend any time on social media, you’ve probably seen the “bullet journal” coming for a while now. Created by Brooklyn digital product designer Rider Carroll, the bullet journal — or “BuJo” to aficionados — purports to be a revolutionary development in personal organization and motivation.

Basically, all one needs to start a bullet journal is a notebook and a nice pen. What makes the system different from a regular old dayplanner is the fact it is a log rather than a to-do list, so it fits anything you’d like to enter into it; and it had an index, which lets the user drill down onto tasks from low resolution (a year out) to high (action by action). It’s also endlessly customizable, which has led to tons of content on sites like Pinterest and Instagram showing off users’ decorative calligraphy and washi-tape-wielding skills.

With BuJoMania sticking around, experts taking a closer look at the system, to see what’s behind its longevity with adopters. According to Cari Romm at The Science of Us, the bullet journal is based on the time-tested strategy of externalizing your thoughts — writing out the things you need to do on paper, so your brain is freed for other tasks. But on top of that, the bullet journal has a twist:

“It’s sort of a spin on environmental cuing, or the concept of placing reminders where you’ll encounter them organically (like placing an umbrella by the door before you go to bed, for example, if you know it’s going to rain the next day). Put your whole life — your work to-dos, your social calendar, your grocery list — in one place, and the odds are higher that you’ll open the notebook for one thing and end up seeing a reminder for something else.”

What I find most interesting about the bullet journal is the fact that it’s so decidedly analogue — a subversion its creator, a digital product designer, must have been acutely aware of. To my mind, that makes the journal’s contents more permanent — so when you change them, you have to acknowledge their former state. The bullet journal ends up being, in addition to a life tool, an interesting metaphor for life.

From counter-top tortilla makers to fridges you can tweet from, so-called “smart” appliances seem to be getting smarter.

But over at Fast Co. Design, writer Mark Wilson posits that the gadgets in our lives are exhibiting the wrong kind of smart — exemplified by his frustrating test drive of the June, “the intelligent convection oven.”

The June boasts an in-oven camera, temperature probe, app connectivity to your phone, and is WiFi capable. It strives to take the guesswork out of cooking by fully automating the whole process. From pre-heating with a button on your touchscreen, to pinging your device when your baked salmon is ready, the June takes control of every aspect of the home cooking experience. This is not good, says Wilson, as it treats the learning and practice of a fundamental life skill (or fun hobby!) as yet another tiresome task that we’re better off handing over to a machine. And to top it all off, this problematic philosophical worldview is packaged in a clunky, buggy shell.

“[T]he June’s fussy interface is archetypal Silicon Valley solutionism. Most kitchen appliances are literally one button from their intended function. […] The objects are simple, because the knowledge to use them correctly lives in the user. […] The June attempts to eliminate what you have to know, by adding prompts and options and UI feedback. Slide in a piece of bread to make toast. Would you like your toast extra light, light, medium, or dark? Then you get an instruction: ‘Toast bread on middle rack.’ But where there once was just an on button, you now get a blur of uncertainty: How much am I in control? How much can I expect from the oven? I once sat watching the screen for two minutes, confused as to why my toast wasn’t being made. Little did I realize, there’s a checkmark I had to press — the computer equivalent of ‘Are you sure you want to delete these photos?’— before browning some bread.”

Wilson’s “buyer beware” about letting the June into our lives can be read as a larger, more ominous warning, about holding onto our human intelligence and autonomy in the face of technological convenience. It’s interesting to consider how many of us are willing to surrender that, to devices from phones on up. What is your limit?

Despite some experts’ developing theories on the impossibility of our ever creating “strong A.I.” — that is, the kind of robot intelligence that we need to worry about getting away from us and eliminating us as threats to itself (ahem Skynet ahem) scientists out there are still plugging away at this fascinating issue.

One way to potentially solve the problem of achieving human-like consciousness is to overhaul the way machines learn, making it more like the method used by human babies and children. At the moment, many machines learn rigidly, systematically testing new input against a vast amount of information already stored. Flexibility in learning, however leads to very fast gains in intelligence, as anyone who’s ever observed a child grow from birth to age four would know! Researchers are now quantifying this human process — a statistical evaluation called Bayesian learning — and applying it to A.I., attempting to reduce the mass of data and time required to gain the same knowledge about the world.

“The new AI program can recognize a handwritten character just about as accurately as a human can after seeing just one example. Using a Bayesian program learning framework, the software is able to generate a unique program for every handwritten character it’s seen at least once before. But it’s when the machine is confronted with an unfamiliar character that the algorithm’s unique capabilities come into play. It switches from searching through its data to find a match, to employing a probabilistic program to test its hypothesis by combining parts and subparts of characters it has already seen before to create a new character — just how babies learn rich concepts from limited data when they’re confronted with a character or object they’ve never seen before.”

The University of Auckland’s Bioengineering Institute is taking this trend in a startling direction, as it works with “BabyX.” BabyX is an A.I. interface that is a 3D animated blonde baby, who can interact with researchers through a screen, demonstrating the real thinking and learning process of the machine intelligence behind it. The interface is essentially one big metaphor for the learning machine, with a bundle of fibre-optic cables as a “spinal cord,” connecting outside input to its “brain.” So BabyX learns by responding to its user as a real baby would to a parent.

“‘BabyX learns through association between the user’s actions and Baby’s actions,” says [project leader and Academy Award-winning animator Mark] Sagar. ‘In one form of learning, babbling causes BabyX to explore her motor space, moving her face or arms. If the user responds similarly, then neurons representing BabyX’s actions begin to associate with neurons responding to the user’s action through a process called Hebbian learning. Neurons that fire together, wire together.’”

All this work really goes to show that something so natural and seemingly simple — the infant human learning process — is actually really complicated, and hard to replicate for a machine. It will be very interesting to see how BabyX, and this new kind of A.I., “grows up” with us.

On Friday, I was happily taking care of the dishes while half listening to a local radio station playing in the next room. Suddenly, over the sound of the running water, I heard the most unholy buzzing screech. I had to turn off the tap and run to the centre of my home to locate it and figure out what it was — Was it an air raid siren? The carbon monoxide detector?!

It took a good couple seconds for me to realize it was coming from my radio, and signaled an active Ontario-wide Amber Alert for a missing Welland girl. When the robot voice started giving the details, I relaxed — but then got to thinking about the effectiveness of the noise in getting me to drop everything and pay attention!

Turns out there are people out there whose job it is to design alarms: and not just to sound so freaky that you freeze and listen, but to make us understand the nature and urgency of the thing we’re being warned about. Plus, they have to circumvent our highly developed brains’ instincts to ignore or disable alarms we have determined to be false or too annoying — with sometimes fatal results. The design specifications are very precise:

“The faster an alarm goes, the more urgent it tends to sound. And in terms of pitch, alarms start high. Most adults can hear sounds between 20 Hz and 20,000 Hz— [designe Carryl] Baldwin uses 1,000 Hz as a base frequency, which is at the bottom of the range of human speech. Above 20,000 Hz, she says, an alarm ‘starts sounding not really urgent, but like a squeak.’

Harmonics are also important. To be perceived as urgent, an alarm needs to have two or more notes rather than being a pure tone, ‘otherwise it can sound almost angelic and soothing,’ says Baldwin. ‘It needs to be more complex and kind of harsh.’ An example of this harshness is the alarm sound that plays on TVs across the U.S. as part of the Emergency Alert System. The discordant noise is synonymous with impending doom.

The Emergency Alert System (have a listen here!) has similarities to the Ontario Amber Alert alarm. But I find the differences really point up what the listener’s reaction should be: to me, the former spells, well, “impending doom,” so I my instinct is to sit calmly and absorb all instructions; and the latter makes me want to get up and do something — like find a child.

The next big project facing alarm designers is forming an “alarm philosophy:” a way of organizing multiple alarms in an environment, so that the most important don’t get drowned out or ignored. Meanwhile, the Amber Alert for Layla Sabry of Welland is officially called off, but she is still missing: familiarize yourself with her case here. And keep your ears open for the next terrifying screech from your radio — someone worked hard to bring it to you!

The Verge has published a moving meditation on a close friendship torn apart by death – and how the friend left behind has memorialized the other in a very 21st century way.

Eugenia Kuyda and Roman Mazurenko became acquainted in Moscow, where he was a cultural mover and shaker, and she wrote for a lifestyle magazine. As the years passed and they grew closer, they fed off each other’s’ entrepreneurial spirit: Roman founded Stampsy, and Eugenia created an A.I. startup called Luka. Roman was well loved in the arts and culture scene, with a bright future ahead of him – until he was struck and killed by a speeding car as he stepped into Moscow crosswalk.

When she felt other methods of memorialization didn’t suit Roman’s personality, or the scale of the grief felt by his friends, Eugenia sought a unique solution. With their permission, she input the lightly edited text and online conversations between Roman and ten friends and family members into a specially built neural network, and created a chat bot that could respond in Roman’s authentic voice. This unexpectedly filled a particularly modern need:

“[In a Y Combinator application before he died] Mazurenko had identified a genuine disconnection between the way we live today and the way we grieve. Modern life all but ensures that we leave behind vast digital archives — text messages, photos, posts on social media — and we are only beginning to consider what role they should play in mourning. In the moment, we tend to view our text messages as ephemeral. But as Kuyda found after Mazurenko’s death, they can also be powerful tools for coping with loss. Maybe, she thought, this ‘digital estate’ could form the building blocks for a new type of memorial.”

Many of Roman and Eugenia’s friends had never experienced the death of someone close to them. But they soon began to engage with the Roman bot in a format they had often used to communicate with the living Roman. The bot matched Roman’s statements to the content detected in the original query. The resulting conversations are really beautiful:

Reactions were mixed – some of Roman’s friends were disturbed and refused to interact with the bot at all, others found that reading their deceased friend’s turns of phrase anew was quite comforting.

As a “digital monument,” the Roman bot continues to be a presence – indeed, anyone who downloads Luka can talk to him in English or Russian. And he – or it – can also be held up as a case study of how our plugged-in society can find new ways to mourn.