To the pantheon of adorable robots, Georgia Tech’s Centre for Music technology is making a bid to add a little fellow named Shimon. With one large lens for a friendly eye and four mallets in hand, Shimon is a demon on the marimba. But while rocking out with the best improvisational jazz musicians, he also shows through mimicry how humans read each other in order to make art.

Shimon can improvise with human musicians by “listening” to them, and following programming to select appropriate complementary beats and notes. But, above and beyond your standard music-generating robot, he also takes in and reflects back particular social cues.

“When you watch a band perform on stage and you observe the guitar player and the drummer synchronizing their movements, you’re actually witnessing an important part of musicianship. […] Body movement, gestures and physical interaction tell musicians how to play their instruments.

[…]Shimon’s intelligence includes an ‘interestingness’ algorithm, where interesting is defined by music that is different from what other players are playing or different from music Shimon heard earlier in a song.

‘And when it does this, he’ll look at you, just like a musician would when you’re playing together, and you do something that was a little off or different,’ [creator Professor Gil] Weinberg said.”

Musicians who jam with Shimon report treating him like a peer: wanting to catch his gaze and while performing and feeling connected to the group as a result.

Beyond the coolness factor, Shimon illustrates how easy it is for a robot to foster human emotional connection. All it takes is a few physical gestures in recognizable shapes, and we fill in the rest. Shimon embodies artistic application, but I could totally see the same principle applied to household helper robots, or even sales robots. Of course, when we get that far…!

I’ve long enjoyed a little light birding as a hobby — but I’ve gotten much more serious about it since moving both home and business to the Frontenac Arch Biosphere and incredibly species-rich area of Canada. Consequently, I’ve also become more interested in the mechanics of conservation — and a recent article in Nautilus introduced me to an aspect of bird self-protection that I’d never considered before.

It’s pretty neat: turns out, the behaviour known as “mobbing” (when groups of smaller birds harass and drive away larger predators from an area) has an important social aspect. Avian wildlife ecologist Katie Sieving (University of Florida) characterizes mobbing as, on the surface, full of risk. The activity calls attention to the birds doing the mobbing, and is distracting enough that another predator could swoop in and pick off a meal with almost no resistance. But chatty, loud, active bird species — in eastern North America, the species is often the titmouse — serve as an early warning system for many species around them, contributing to a general understanding that the area is a “good neighbourhood.” Other species (including small mammals) literally “eavesdrop” on the titmice, and:

“[t]his eavesdropping turns out to be adaptive. Multiple studies have demonstrated that social and talkative bird species, the ones most likely to initiate mobbing, improve the survival of the birds around them. Titmice, tits, chickadees, fulvettas: They’re tiny birds with big mouths, and wherever they live, less outspoken species are drawn to them, and eat better, have more babies, and live longer. Sieving says, ‘We don’t know if it’s a kind of parasitism’ — that is, the bolder species are actually harmed by the shyer species’ use of their vigilant habits; ‘or if it’s just commensalism’ — the shyer species benefit, but the bolder species are not affected.

Either way, these dynamics seem essential to community structure.”

This behaviour is so valued by other species that they will follow their virtual canaries in the mine to other locations — which is helping scientists refine the efficacy of wilderness corridors, and other human-created strategies for bird survival in an anthropocentric world.

Right now, as mentioned earlier, I’m having a great time working with the Elbow Lake Environmental Education Centre on a series of workshops on using tech to help identify all the amazing birds that call our home “home.” I’m hoping, at the next session when I’m chatting with an attendee, or if I’m out and about, to catch a little “mob” activity — giving me the chance to see such a seemingly straightforward behaviour in a much more far-reaching light!

As a devoted dog person, I have long thought that my two pack-mates, Jill and Samson try to communicate with me vocally. (Jill especially, who is a howler more that a barker, can be quite articulate in her criticisms when I’m a bit too slow getting her dinner ready!) But, of course, they can’t really be capable of conversation, can they? They’re dogs — and research has proven that even primates who are animals more closely related to us don’t possess throat and mouth structures that allow for speech.

That was the prevailing idea even two months ago; but new research is now calling into question humanity’s monopoly on intelligible speech. First, scientists out of the University of Vienna and Princeton University tested live macaques’ vocal tracts and found them to be capable of replicating the sounds needed for human speech. (The previously accepted research that said they weren’t was based on dissections of deceased specimens.) Along with their study, published in ScienceAdvances, the team released audio of what a macaque, if it also had the necessary neural capacity, would sound like speaking English. (Bonus questioning-how-different-we-truly-are points by having it ask “Will you marry me?”!)

Now, a French team who studied baboons, not macaques, has discovered that they too are naturally able to produce all the distinct vowel sounds found in human languages. That indicates that the ability to speak is more widely dispersed among our animals relatives, and may have been cooking in our genetic code since before our split from other primates. More work from the Max Planck Institute supports this too:

“Whatever sounds make up a vocal repertoire — vowels, consonants, grunts or basic barks — humans were once thought the only primate able to control their voices to any significant extent. Other animals were thought to make sounds like you yelp when you touch an iron: as pure reflex.

But in a 2015 study, [cognitive scientist affiliated with the Max Planck Institute Marcus] Perlman and a team of researchers documented how a 280-pound gorilla named Koko had been trained to cough, blow into a recorder and make several other noises at will.

His team’s study was followed up last year, when an orangutan named Rocky at the Indianapolis Zoo was trained to control something approximating a voice.

‘He was able to listen to a human make a vocalization and able to match the frequency of that,’ said Rob Shumaker, who is the zoo’s executive vice president and co-authored the study. ‘Prior to this study with Rocky, most of the conversation was saying this is a uniquely human event.’”

Some folks are getting excited about the possibilities of other, non-human species’ capacity for speech — but still recognize that a parrot asking for a cracker, or cat yelling “No!” would not shed light on the relation between our evolution and our ability to make ourselves understood. I’d be happy if it would shed light on exactly what Jill is cursing me with when I chastise her for opening the front door in the middle of the night. But we’ll start with this exciting development with primates first, and see how it goes!

A study out of the School of Management and Business at King’s College London has proven something that, anecdatally, also makes a lot of sense — that conscientious, above-and-beyond-type employees, who are successful at their jobs because of this drive, also experience significant emotional exhaustion, and struggle to keep a work-life balance.

Participants in the study, all workers in a UK bank’s inbound call-centre, reported feelings of being drained and “used up.” This was often because of workplace policies, that, in today’s age of tenuous employment with vaguely defined boundaries, called on participants to go beyond their job descriptions.

While participants were frequently rewarded for their “organizational citizenship behaviour,” in the form of being considered for raises, job advancement, and being thought of as generally dependable, this goodwill had a dark side.

“Conscientious workers have been noted for their dependability, self-discipline and hard work, and their willingness to go beyond the minimum role requirements for the organization. They are also said to make a greater investment in both their work and family roles and to be motivated to exert considerable effort in both activities (not wanting to “let people down”), thus increasing work-family conflict and leaving them with little resource reserve. […]

Our study shows that a possible overfulfillment of organizational contributions can lead to emotional exhaustion and work-family conflict. […] Managers are prone to delegate more tasks and responsibilities to conscientious employees, and in the face of those delegated responsibilities conscientious employees are likely to try to maintain consistently high levels of output. […] The consequences, however, may be job-related stress and less time for family responsibilities.”

I do wonder if the fact that they drew from a pool of employees in an already emotional-labour heavy industry made the study’s results even starker. It will be interesting to see if further research into other types of work, as the study’s conclusion calls for, might uncover the same trends. I know that in my working life, I myself have seen firsthand proof of the adage “If you want something done, ask a busy person.” This study shows that, similarly, “If you want something done well ask a conscientious person” — but maybe now we have a responsibility to think about the personal fallout of that request.

With the veritable explosion of technology and online platforms in recent decades, research is understandably catching up to the core truths about how our (comparatively un-evolved) brains and bodies interact with these almost parallel realities. One narrative has us at the mercy of insidious tech that erodes our willpower and enslaves us to our glowing blue screens. But new research involving twins and social media use is shedding light on a possible genetic component to our online habits — and, paradoxically, showing us how a lot of it can be modulated by choice.

The new study, authored by researchers at King’s College London, and published recently in the journal PLOS ONE analyzed online media use of 8500 teenage twins, both identical and fraternal. By comparing their behaviours and the amount of genes they shared (identical twins share all, and fraternal half), the researchers were able to determine how much of their online engagement was nature, and how much nurture. The (rather complicated!) equation is as follows:

“Heritability (A) is narrowly defined as the proportion of individual differences in a population that can be attributed to inherited DNA differences and is estimated by doubling the difference between [identical] and [fraternal] twin correlations. Environmental contribution to phenotypic variance is broadly defined as all non-inherited influences that are shared (C) and unique (E) to twins growing up in the same home. Shared environmental effects (C) are calculated by subtracting A from the [identical] twin correlation and contribute to similarities between siblings while non-shared environmental effects (E) are those experiences unique to members of a twin pair that do not contribute to twin similarity.”

The results found that a great deal of heritability was at play for all types of media consumption, including entertainment (37%); educational media (34%); gaming (39%); and social networking, particularly Facebook (24%). At the same time, environmental factors within families were the cause of two-thirds of the differences in siblings’ online habits. That indicates that while we are what our genes are, their in-world expression can be molded by free will. A heartening thought for a species buffeted by so much technological change!

|

We’re lucky enough to be surrounded by so much gee-whiz tech nowadays – from the Mars rover to tortilla Keurigs – that it’s easy to forget that the definition of technology includes some elegantly simple concepts. The lever, the wedge and the pulley have all changed the world far beyond what their uncomplicated structures might indicate possible. We have learned that in simplicity lies a wealth of usefulness – and an amazing new lab tool with world-changing potential is demonstrating this to us yet again.

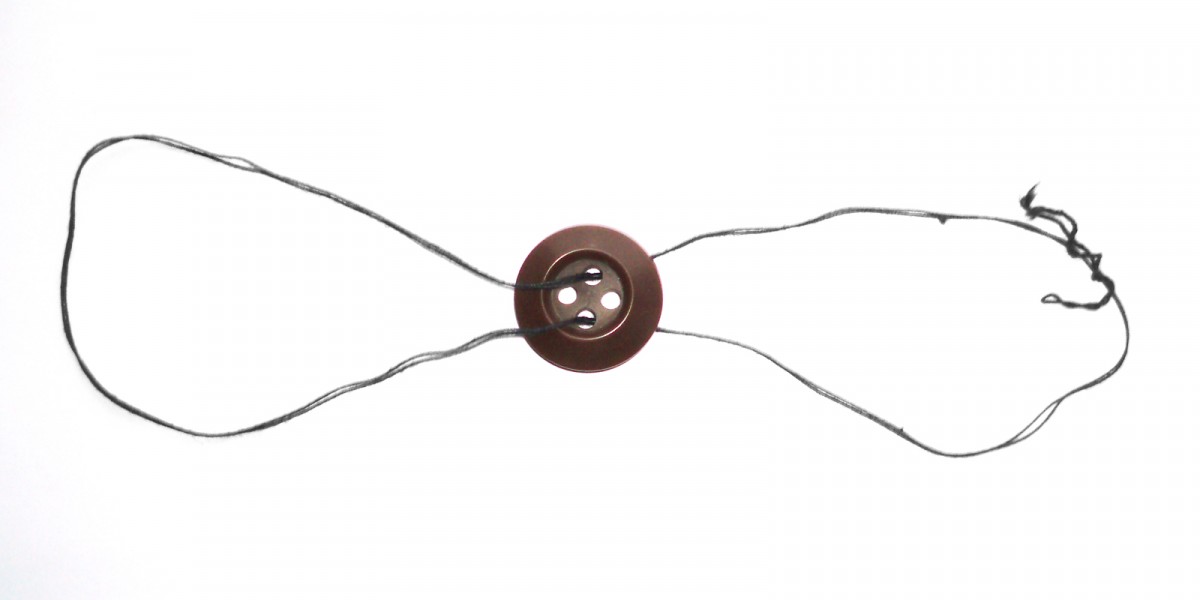

Stanford bioengineer Manu Prakash, of Foldscope and “frugal science” fame, and his team, have created an incredibly portable, outrageously inexpensive human-powered centrifuge, adapted from a popular and ancient toy design: the whirligig. A whirligig is essentially a paper disk or button, which, when suspended on a looped string that is pulled outward with the hands, spins quickly in the middle. Prakash’s “Paperfuge,” nearly identical in design, can spin hard enough to separate plasma from blood cells in 90 seconds. This allows important diagnostic procedures to be carried out quickly in clinics that may lack the electricity, funds, or infrastructure to obtain and use standard centrifuges. Faster diagnosis means faster help for patients in remote communities. The problem of a frugal centrifuge was longstanding: researchers had already tried adapting a salad spinner and an egg-beater into devices that were still too complicated to be effective and cheap. Then post-doc Saad Bhamla remembered a toy from his childhood that seemed suddenly promising: “They discovered that much of the toy’s power hinges on a phenomenon called supercoiling. When the string coils beyond a certain threshold, it starts to form another coil on top of itself. […] Physical prototypes came next. They tweaked the length of the string and the radius of the disc, and tried a variety of materials, from balsa wood to acrylics. In the end, though, the group settled on the same stuff Prakash used to build his Foldscopes . ‘It’s synthetic paper, the same thing many countries use in their currency,’ Prakash says. ‘It has polymer films on both front and back that make it waterproof, and it’s incredibly strong, as well.’” The Paperfuge removes critical barriers to access to diagnosis of many diseases, including malaria and HIV. In addition to the cool factor of a beloved childhood toy being repurposed for a higher calling, its existence will help prevent many deaths, and increase quality of life for huge segments of the world population. And that, I think, is the truest and best use of any technology. |

Curiosity may have killed the cat, but it might also breathe life into human workers’ careers — a different breed of curiosity, at least, that researchers are just starting to look at.

In a recent study done by the University of Oklahoma, Oregon State University, and Shaker Consulting Group, researchers have discovered the connection between “diversive curiosity” and flexibility in problem solving. Diversive curiosity is a trait that occurs in varying strengths in most people: those with stronger tendencies collect more and wider-ranging information in the early stages of approaching a problem, and exhibit greater plasticity in applying that information.

This type of curiosity is highly prized in the employees in today’s increasingly complicated workforce, as it directly results in a greater capacity for creative problem solving. On the other hand, “specific curiosity” — the kind that mitigates anxiety and fills particular, rigidly defined gaps in knowledge, is a trait that, in its strength in a subject, indicates a less-creative approach.

“[…R]esearchers asked 122 undergraduate college students, to take personality tests that measured their diversive and specific curiosity traits.

They then asked the students to complete an experimental task involving the development of a marketing plan for a retailer. Researchers evaluated the students’ early-stage and late-stage creative problem-solving processes, including the number of ideas generated. The students’ ideas were also evaluated based on their quality and originality.

The findings indicated that the participants’ diversive curiosity scores related strongly to their performance scores. Those with stronger diversive curiosity traits spent more time and developed more ideas in the early stages of the task. Stronger specific curiosity traits did not significantly relate to the participants’ idea generation and did not affect their creative performance.”

The researchers further discovered that lots of companies post job listings searching for candidates with creative problem solving skills, but often don’t end up hiring people who really have them. Now that the type of curiosity that correlates with those skills has been defined, personality tests can be used to identify the most successful candidates — leading to better “cast” employees, and happier humans and companies!

Throwing myself back into my standard working hours after a holiday period off has really made me think about how much we in the business world try to manage our sleep. We at DFC are able to set our own hours, but some hours are non-negotiable: my canine alarm clocks certainly don’t know the difference between four a.m. on a holiday and four a.m. on the day of an important client presentation. I do, and my quality of sleep is definitely different!

Because technology is advancing so quickly, we constantly find ourselves having to re-frame or re-approach ancient physical necessities like sleep. Over at The Atlantic, physician James Hamblin works through some of the big forces affecting sleep in our busy era. He comes uncovers some hard truths: some people are wired to excel on four hours of sleep, but most aren’t; and Red Bull can kill you!

But it’s not all doom and gloom. My favourite “hack” involves s deceptively simple action – putting your phone away at least an hour before bed. The sleep-killing effects of late-night screen time are well known, but Hamblin breaks down the brain science particularly vividly:

“When light enters your eye, it hits your retina, which relays signals directly to the core of your brain, the hypothalamus […] the interface between the electricity of the nervous system and the hormones of the endocrine system. It takes sensory information and directs the body’s responses, so that the body can stay alive.

Among other roles in maintaining bodily homeostasis—appetite, thirst, heart rate, etc.—the hypothalamus controls sleep cycles. It doesn’t bother consulting with the cerebral cortex, so you are not conscious of this. But when your retinas start taking in less light, your hypothalamus assumes it’s time to sleep. So it wakes up its neighbor the pineal gland and says, ‘Hey, make some melatonin and shoot it into the blood.’ And the pineal gland says, ‘Yes, okay,’ and it makes the hormone melatonin and shoots it into the blood, and you become sleepy. In the morning, the hypothalamus senses light and tells the pineal gland to stop its work, which it does.”

I’ve now taken to leaving my phone charging in another room as I sleep, and going back to a regular old alarm clock (remember those?) — for my bedside table, so I don’t blast my hypothalamus with blue light as I check the time. At the moment, I don’t feel the need to experiment with caffeine or melatonin, or any of the other interventions Hamblin describes. But you may — give the article a read and let us know what you think! Meanwhile, I will try reading it to Jill and Samson, to see if they will finally, finally understand what they are doing to me.

If you spend any time on social media, you’ve probably seen the “bullet journal” coming for a while now. Created by Brooklyn digital product designer Rider Carroll, the bullet journal — or “BuJo” to aficionados — purports to be a revolutionary development in personal organization and motivation.

Basically, all one needs to start a bullet journal is a notebook and a nice pen. What makes the system different from a regular old dayplanner is the fact it is a log rather than a to-do list, so it fits anything you’d like to enter into it; and it had an index, which lets the user drill down onto tasks from low resolution (a year out) to high (action by action). It’s also endlessly customizable, which has led to tons of content on sites like Pinterest and Instagram showing off users’ decorative calligraphy and washi-tape-wielding skills.

With BuJoMania sticking around, experts taking a closer look at the system, to see what’s behind its longevity with adopters. According to Cari Romm at The Science of Us, the bullet journal is based on the time-tested strategy of externalizing your thoughts — writing out the things you need to do on paper, so your brain is freed for other tasks. But on top of that, the bullet journal has a twist:

“It’s sort of a spin on environmental cuing, or the concept of placing reminders where you’ll encounter them organically (like placing an umbrella by the door before you go to bed, for example, if you know it’s going to rain the next day). Put your whole life — your work to-dos, your social calendar, your grocery list — in one place, and the odds are higher that you’ll open the notebook for one thing and end up seeing a reminder for something else.”

What I find most interesting about the bullet journal is the fact that it’s so decidedly analogue — a subversion its creator, a digital product designer, must have been acutely aware of. To my mind, that makes the journal’s contents more permanent — so when you change them, you have to acknowledge their former state. The bullet journal ends up being, in addition to a life tool, an interesting metaphor for life.

From counter-top tortilla makers to fridges you can tweet from, so-called “smart” appliances seem to be getting smarter.

But over at Fast Co. Design, writer Mark Wilson posits that the gadgets in our lives are exhibiting the wrong kind of smart — exemplified by his frustrating test drive of the June, “the intelligent convection oven.”

The June boasts an in-oven camera, temperature probe, app connectivity to your phone, and is WiFi capable. It strives to take the guesswork out of cooking by fully automating the whole process. From pre-heating with a button on your touchscreen, to pinging your device when your baked salmon is ready, the June takes control of every aspect of the home cooking experience. This is not good, says Wilson, as it treats the learning and practice of a fundamental life skill (or fun hobby!) as yet another tiresome task that we’re better off handing over to a machine. And to top it all off, this problematic philosophical worldview is packaged in a clunky, buggy shell.

“[T]he June’s fussy interface is archetypal Silicon Valley solutionism. Most kitchen appliances are literally one button from their intended function. […] The objects are simple, because the knowledge to use them correctly lives in the user. […] The June attempts to eliminate what you have to know, by adding prompts and options and UI feedback. Slide in a piece of bread to make toast. Would you like your toast extra light, light, medium, or dark? Then you get an instruction: ‘Toast bread on middle rack.’ But where there once was just an on button, you now get a blur of uncertainty: How much am I in control? How much can I expect from the oven? I once sat watching the screen for two minutes, confused as to why my toast wasn’t being made. Little did I realize, there’s a checkmark I had to press — the computer equivalent of ‘Are you sure you want to delete these photos?’— before browning some bread.”

Wilson’s “buyer beware” about letting the June into our lives can be read as a larger, more ominous warning, about holding onto our human intelligence and autonomy in the face of technological convenience. It’s interesting to consider how many of us are willing to surrender that, to devices from phones on up. What is your limit?