For all our vaunted advantages — thumbs! giant brains! — the human toolbox sometimes pales in comparison to all of the species-specific hardware out there. For example, whiskers are an extraordinary set of close-range sensing organs that are found not only on the usual suspects of cats and dogs, but on rodents, seals, and even some birds. Whiskers allow their bearers to feel objects around them and orient themselves spatially (as in a tunnel), as well as to detect wind speed and direction.

What humans are really good at, though, is borrowing cool concepts from the natural world for use in robotics. And that is exactly what is happening with whiskers. A team out of the University of Queensland is investigating how to equip small drones with cute-but-functional vibrissae, to provide a low-cost physical sensor for inexpensive robots.

The drone whiskers are made by heating dots of ABS plastic and drawing them out into fine threads. Mounted on force pads, and then on the drone, the whiskers boast a whole range of sensing capabilities to be tested.

“We are interested in translating the proven sensor utility of whiskers on ground platforms to hovering robots and drones— whiskers that can sense low-force contact with the environment such that the robot can maneuver to avoid more dangerous, high-force interactions. We are motivated by the task of navigating through dark, dusty, smoky, cramped spaces, or gusty, turbulent environments with micro-scale aircraft that cannot mount heavier sensors such as lidars.”

Though they are not as accurate in long-distance sensing as lidar or cameras, plastic whiskers are cheap. Their use in small, light drones that may be sent into situations they’re not going to come out of in one piece is a perfect match of form and function. I for one welcome our new adorable robot overlords — as do Jill and Samson, the original whisker-havers!

Animal testing is an unfortunate reality of how we make biomedical research happen. While organizations have struggled to drive down cosmetic testing and other non-critical uses of animal lives, animal testing in medicine and the sciences is a necessary evil. (Though it can be debated how much of the foot-dragging is because there really are no viable alternatives)

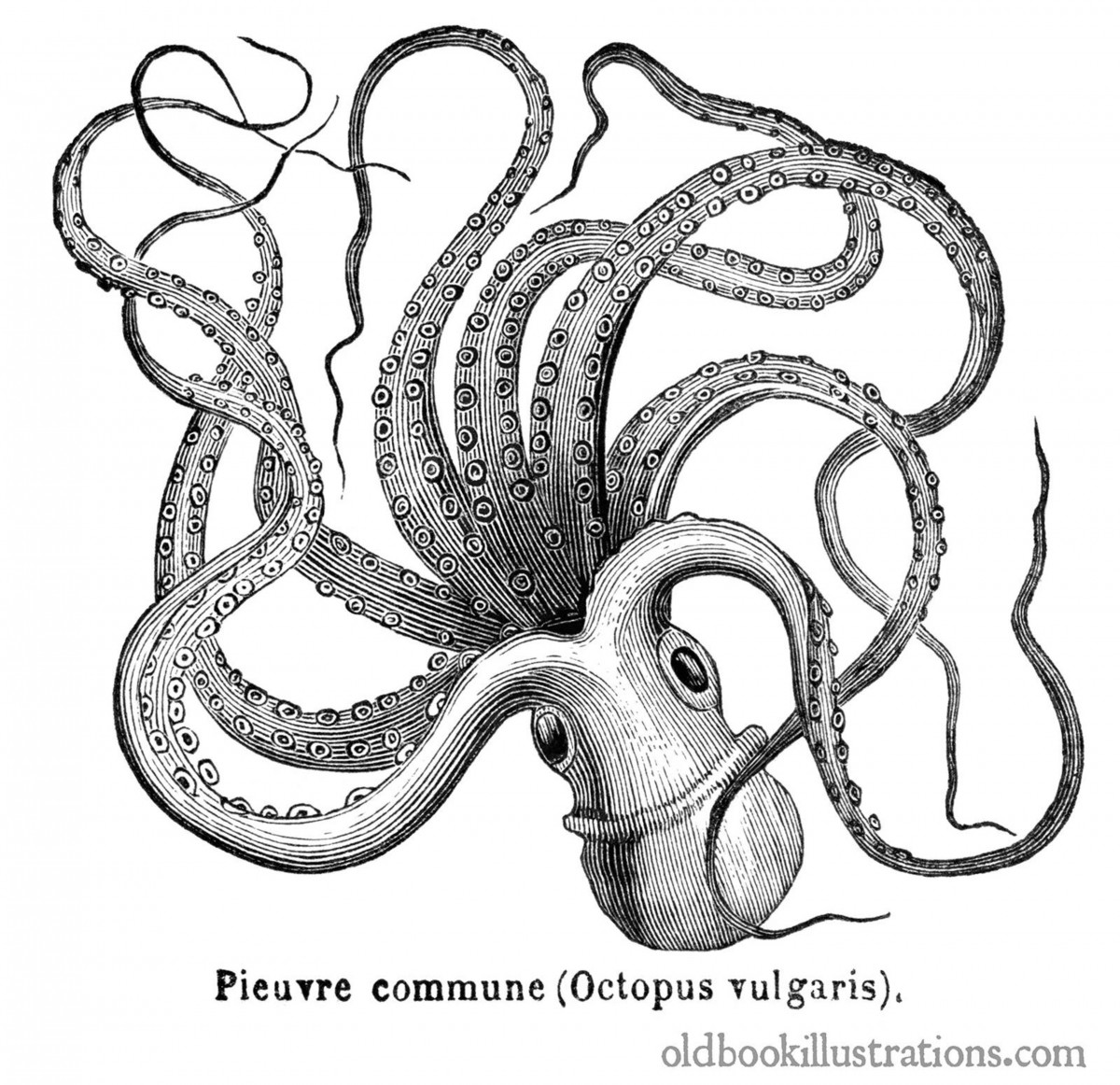

But I wonder if this might change, now that researchers are looking to replace the standard “lab rat” with one of the most fascinating classes of animals, Cephalopoda — that is the octopus, cuttlefish, and squid. Scientists are interested in the unique makeup of these amazing creatures and want to learn more about how they react to their environments. Plus, they are taking their new ethical ground seriously: Cephalopods, some of which are “the closest we will come to meeting an intelligent alien” are governed by similar experiment rules that protect fruit flies, worms, and other invertebrates. Will that be enough to protect these mysteriously intelligent creatures as we strive to understand them?

The Marine Biological Laboratory is making the attempt. NPR reports:

“‘I ended up sequencing the [California two-spot] octopus genome because I’m interested in how you make a weird animal,’ says Carrie Albertin, who now works at MBL. ‘Most of their genes have some similarity to genes that we have and other animals have. Their close relatives are clams and snails. But they seem just so otherworldly.’ […]

Knowing all the genes is just a start for researchers interested in these animals. The obvious next step is trying to tinker with those genes, to see what happens if they’re disrupted. […]

Figuring out how to do this has been labor-intensive. Research assistant Namrata Ahuja sits at a microscope, where she injects gene-editing material into tiny squid embryos over and over and over again.

‘You get embryos almost every day, and their clutch that they lay can vary anywhere from 50 to 200 eggs in one clutch,’ she explains. ‘So if you get that many in one day, for five days a week, that adds up.’”

Research into these animals can yield fascinating insight into their behaviour. In addition, the more we learn about the octopus, the more we can describe the boundaries of human nature — while the evolutionary branches of cephalopods and humans on the tree of life diverged long ago, the study of octopuses, in particular, is illuminating because “evolution built minds twice over.”. The MBL team is spearheading anaesthesia research to keep these critters comfortable and unexploited. If those qualifications are met, who knows what wonders Cephalapoda can help us unlock?

We at DFC have cleaned a lot of mystery residues off of hardware in our time. Cherry cola in a keyboard, lunch grease in a trackball, corrosion of all kinds — you name it, we’ve pried it off some computer part.

Thankfully, we’ve never come across a cleanup job like Eliot Curtis did recently. A broadcast operations manager at the San Francisco CBS station, as well as a hacker in his private life, Curtis volunteered to restore a Buchla Model 100 synthesizer for California State University East Bay  Campus. A model of early synthesizer that helped usher in the 1960s mania for electronically generated music, this particular instrument had been languishing in storage since the fad passed.

Campus. A model of early synthesizer that helped usher in the 1960s mania for electronically generated music, this particular instrument had been languishing in storage since the fad passed.

But Buchla Model 100s were also the nexus of a particularly groovy rumour: Designer Don Buchla had connections that cooked up some fabulously powerful LSD, and some Buchla synths, owned by Ken Kesey, were reputed to have had components coated in acid by his Merry Pranksters.

Curtis began cleaning this particular real-life synthesizer and came right up against this rumour — physically.

“As Curtis was disassembling a module that appears to have been added to the Buchla Model 100 after it was delivered to the school, he noticed a crystal-like residue stuck under one of the instrument’s knobs. In an attempt to dislodge it, he blasted it with cleaning solvent and tried to simply rub it off with his finger. Forty-five minutes later, he started to experience a tingling sensation, the beginnings of an acid trip, that would last nine hours. Three separate chemical tests later identified the crystallized substance as lysergic acid diethylamide — or LSD — which can be absorbed through the skin, and can survive for decades.”

As a former chemist, I find this story fascinating and went on a deep dive into the varying opinions on how long LSD can last in the open air. Most commenters on Curtis’s accidental trip claim it’s a tall story: LSD is pretty unstable in its pure form, and in its most common format — a liquid, usually soaked into the absorbent paper. Exposure to heat, light, and oxygen over a large surface area can cause it to break down within months.

However, pure acid was frequently stabilized with additives before sale. Additionally, the relatively large mass of crystallized acid found under the Buchla knob could retain potency deep in its centre, especially in the cool, dark, and undisturbed conditions in which the synth was stored.

From inspiring musicians and Silicon Valley innovators to alleviating end-of-life anxiety, LSD has many uses. Add to this list an excuse to bunk off work for nine hours! Kidding aside, getting dosed without preparation can be scary. Whatever Curtis’s experience was, I’m glad he made it out intact, to service many future synths — with gloves on, next time.

If you’re anything like me — an apian layperson — when you hear the word “bee,” your mind immediately fills with terrible visions of colony collapse disorder, leading to no more honey, and then leading to the end of all life on earth.

But, if you’re anything like me — an environmental catastrophizer — you’ll also have made a bit of a leap in logic in the above paragraph. Honey bees, with their industrious culture and their cute looks, are the poster children for the bee-pocalypse that threatens our world. But, they are only one of the nearly 20,000 species of bee that plies the skies worldwide, and are relatively new to Ontario (home to 400 bee species!). Our plants and crops are pollinated by many, many creatures of varying precarity, but the honey bees are doing remarkably okay — and that’s a problem for everyone else. Bloomberg has a fascinating pocket-cast on this phenomenon and cites biology professor David Goulson’s frustration.

“Honeybees are essentially livestock, Goulson says. They’re kept in manmade structures where they’re given food and medicine, and then they’re deployed by the millions to perform a specific agriculture function. All that special treatment makes them a poor symbol for the environmental problems faced by the many other species of bee, he says.

‘I get really frustrated when people talk about “the bee,”’ Goulson says. ‘They’re usually talking about honeybees, or maybe they’re just talking about bees and they don’t realize there’s more than one species.’”

All bees do benefit from the attention drawn by the charismatic honey bee, it’s true. But it’s imperative that differences in species be respected when it comes to human interventions. I’m thinking of the phenomenon of bee hotels: little houses made of untreated wood, with holes of varying size drilled in to provide shelter for colony-less mother bees and their eggs.

Piloted in Amsterdam in 2000, the hotels, and corresponding intensive plantings of local flora, are responsible for increasing the local bee population by a whopping 45%. Now trending worldwide, bee hotels in private gardens and in parks must be designed with local species in mind: to use the Dutch example, tube nesting bees number only three species, and will refuse to nest in tubes that are not 2mm to 10mm in diameter. Larger holes permit colonization by parasitic wasps and flies, and provide a foothold for mould — defeating the purpose of an insect refuge entirely!

I’m tempted to do my research and build a little bee hotel chez DFC since I was given instructions here on how to build one. Even if the honey bees in our community don’t need it, I’d love to help out some of the other species that take care of pollinating our food and flowers. I deeply appreciate their efforts — and, if I get the design right, they will hopefully appreciate my efforts in return.

Among the many reasons why I’m glad I’m my own boss, knowing I’ll never fire myself for being obsolete ranks high! But there are many jobs out there that are threatened by mass automation — from the obvious data entry gigs and telemarketing to the startling library technician jobs, and, I’m sure, personal assistants.

But new research is showing that replacing all human employees in industrial working environments with automation is — against all assumptions — not the most efficient option.

A co-pro between the Universities of Göttingen, Duisburg-Essen, and Trier, the study has recently been published in the International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technologies. In it, the team presented a challenge to three different teams of workers, sporting varying levels of automation.

“The research team simulated a process from production logistics, such as the typical supply of materials for use in the car or engineering industries. A team of human drivers, a team of robots and a mixed team of humans and robots were assigned transport tasks using vehicles. The time they needed was measured. The results were that the mixed team of humans and robots were able to beat the other teams; this coordination of processes was most efficient and caused the fewest accidents. This was quite unexpected, as the highest levels of efficiency are often assumed to belong to those systems that are completely automated.”

These results give a ray of hope to humans currently working in industrial fields who have thought, until now, that robots would be taking over their positions. The combo — of human logistical capacity, and the tolerance of repetitive tasks — could be well nigh unstoppable.

This is certainly a rosier vision of the automated future than we have been led to believe. While we’re nowhere near the fifteen-hour workweek predicted by John Maynard Keynesin the early 20th century, neither are we staring down the barrel of life under Skynet. Here’s to a future for both humans and robots, working together to make life better for all!

I love this part of spring — all the early snowdrops and crocuses have had their time, and the gardens are now filled with my favourites: showstopping tulips. It’s early enough that I’m still surprised by their presence. Soon we’ll be seeing all kinds of wonderful summerflowers in our neck of the woods, including roses of all stripes.

A team out of the University of Texas at Austin has taken inspiration from nature and looked to the rose for help with one of humanity’s biggest problem: sourcing clean water. The team sought a more efficient method of solar steaming — a process by which the heat of the sun is used to evaporate water up and away from contaminants, then collected and condensed back into clean drinking water. (Much like the principle of the solar still in that episode of Voyage of the Mimi.)

Current solar steaming technology is generally bulky and stationary. In order to have a real effect on water quality and availability in places it’s needed, portability and efficiency are key. The new system attempts to remedy this. As outlined by the team in a recent issue of Advanced Materials the solar steamer is inspired by an origami rose, featuring “petals” made of black paper coated with polypyrrole, all surrounding a collection tube that acts much like a stem. From UT Austin’s press release:

“[Leader Donglei (Emma)] Fan and her team experimented with a number of different ways to shape the paper to see what was best for achieving optimal water retention levels. They began by placing single, round layers of the coated paper flat on the ground under direct sunlight. The single sheets showed promise as water collectors but not in sufficient amounts. After toying with a few other shapes, Fan was inspired by a book she read in high school. Although not about roses per se, ‘The Black Tulip’ by Alexandre Dumas gave her the idea to try using a flower-like shape, and she discovered the rose to be ideal. Its structure allowed more direct sunlight to hit the photothermic material – with more internal reflections – than other floral shapes and also provided enlarged surface area for water vapor to dissipate from the material.”

The device decontaminates the water from bacteria, heavy metals, and sea salt, and makes it fit for human drinking according to standards set out by the World Health Organization. Again, science looks toward the designs of nature for solutions to our problems. It is fitting that the rose — the harbinger of summer, subject of poetry carrier of centuries of symbolism — should find its form harnessed for our very human needs!

Here at the DFC ranch, we don’t have to come up with excuses that dogs make office and home life better: we have reasons — a pair of them. The dogs get us away from our desks when our eyes and backs need a break, and inject much-needed levity into our workdays. (The fact that Jill can open doors, and is vocal enough to interrupt any conversation she dang well pleases — her foundation stock includes malamute, god help us — is hilarious.)

Beyond these immediate, quality-of-life-improvement reasons, we haven’t given much thought to the underlying impulse toward dog ownership. But the people at Uppsala University have: and by using data from the famed Swedish Twin Registry, they’ve uncovered the startling results that being a “dog person” can be predetermined by your genes.

The team focused on 85,542 individuals in monozygotic and dizygotic (that is, identical and fraternal) twin pairs, who were born between 1926 and 1996, and who were both still alive. They compared the collected data on the twins with stats on dog ownership between 2001 and 2016, as registered with the Swedish Board of Agriculture and the Swedish Kennel Club.

“Studying twins is a well-known method for disentangling the influences of environment and genes on our biology and behaviour. Because identical twins share their entire genome, and non-identical twins on average share only half of the genetic variation, comparisons of the within-pair concordance of dog ownership between groups can reveal whether genetics play a role in owning a dog. The researchers found concordance rates of dog ownership to be much larger in identical twins than in non-identical ones — supporting the view that genetics indeed plays a major role in the choice of owning a dog.”

The complicated modeling the team undertook is all in their study, published in full here. But, all in all, it shows that heritability of dog ownership runs at 57% for females and 51% in males (in Sweden). This tendency could also help explain why dogs were domesticated so early in our history — and how their own genomes morphed to make living with us more viable. I knew Jill and Samson’s hold on us was stronger than they were letting on!

Working with computers can be pretty esoteric — after all, the reason why DFC exists as a professional team is because folks who prefer to focus on other things need our network-wrangling, cloud-tapping expertise (link: http://dfc.com/solutions/). That is the very same reason I have an accountant, and my accountant, in turn, has a dentist: everyone has a speciality; one that is often a mystery to the other professions!

Despite their differences, one commonality that I think ties together professionals of all stripes is a love of craft. I see this in the care David takes over the creation of our line of sauces. I see it in artist friends who put so much effort into the selection of a brush or photo negative. And, I saw it in a charming video from the Great Big Story people, about one of the most esoteric professions, mathematics, and how practitioners of the abstract science are OBSESSED with, of all tools, chalk.

Specifically, a Japanese brand of chalk, called Hagoromo Fulltouch, so prized for its smoothness, density, and line that one user dubs it “the Rolls Royce of chalk.” Mathematician David Eisenbud describes the almost cult-like initiation he had into the knowledge of Hagoromo chalk fondly:

“I discovered it when I went to visit the University of Tokyo and one of the professors there said to me, you know, we have better chalk than you do in the States and I said, oh go on, chalk is chalk. And so I tried it out, and I was surprised to find that he was right.”

Hagoromo chalk became something of MacGuffin for high-level mathematicians, and with its popularity being driven almost as much by scarcity as its near-metaphysical writing properties. Users across the world relied on business trips to Japan or sympathetic Japanese colleagues to maintain their supply — until the company went out of business in 2015. Says Professor Brian Conrad:

“I sort of jokingly referred to it as a chalk apocalypse. So I immediately started hoarding up as much as I could. […]

I was probably selling it regularly to maybe eight to 10 colleagues. I would reach into my cupboard in my office and pull out another box and we’d do the deal in my office. Yeah, we all had a chalk fix. And we still do.”

A Korean company bought up Hagaromo’s manufacturing machinery and formula, so the critical moment of the chalk’s extinction has been delayed. But the hoarding described by Prof. Conrad firmly underscores the close relationship between the practice of a profession — or an art — and even the most mundane of tools. The simplest solution can dissolve the barrier between a creator and the Zone; a piece of chalk can unlock a complicated theorem. What simple tool in your everyday arsenal is your Hagaromo chalk?

This Passover I indulged in one of my favourite holiday-themed activities, next to cathartically cleaning house: watching the classic 1956 movie epic The Ten Commandments. Between bouts of arguing the relative acting abilities of Yul Brynner vs Chuck Heston (Brynner for the win!), we got to talking about all the theories about the building of the pyramids. When I went to school, the leading theory involved thousands of slaves — much like the Israelites — using a series of dirt ramps to elevate the giant stone blocks required. (My daughter-in-law, on the other hand, is firmly in camp Ancient Aliens)

Though the Israelites in The Ten Commandments (and in the original source) weren’t on pyramid duty, slave labour was definitely a part of Ancient Egyptian society. But scholars have shown that specifically the Great Pyramids were more likely constructed by well-compensated artisans rather than slaves.

How they did it is another mystery to be unraveled; but I wonder if there was some engineering magic at foot, like that recently wrought by researchers at MIT and sculptors at Matter Design. These innovators have created a fascinating set of 3900 lb concrete bricks, which are so precisely calibrated that they can easily be moved by one or two people. This project, called Walking Assembly, was undertaken to explore how ancient peoples might have made their monolithic structures well before the invention of the crane. From the project description:

“Walking Assembly re-introduces the potentials of that ancient knowledge to better inform the transportation and assembly of future architectures. If a brick is designed for a single hand, and a concrete masonry unit (CMU) is designed for two, these massive masonry units (MMU) unshackle the dependency between size and the human body. Intelligence of transportation and assembly is designed into the elements themselves, liberating humans to guide these colossal concrete elements into place.”

The giant bricks are made out of variable-density concrete, which makes for an exact centre of gravity. Builders then tilt and roll the bricks into assemblages like walls and staircases. Check out the video of Walking Assembly in action here!

The designers also cite play as a key aspect of their creation — and the manipulation of the bricks looks fun, in a jungle gym kind of way! It’s possible ancient builders, enslaved or artisans found ways of engineering their materials for maximum efficiency in the way these modern creators do. Whether they had fun is anyone’s guess.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that there are some things you can DIY, and some things you can’t. I myself grew up in a very handy household, but even my father handed down the sage advice of always hiring a professional for at least two aspects of maintenance: electricity and plumbing. Pallet planter? Go ahead. Roman blind? Have at it. But anything involving serious risk to life and limb was out.

Which is why I am full of admiration for the inventiveness of a certain homebrew community I read about this week. In the Soviet Union, car ownership was sporadic and limited to the basic, quasi-nationalized brands of cars that were less than reliable and even less than affordable. So, what was an Eastern Bloc car enthusiast to do? According to Jalopnik, build their own — from harvested parts, chunks of other machines entirely, and raw materials like fiberglass and glue. Misha Lanin writes:

“Resources aside, each homemade car is an incarnation of the creator’s automotive dreams, whatever they may have been — air scoops and spoilers and three-figure top speeds, morning commutes not on the dinky trolleybus, family mushroom picking trips deep into the woods.

Like the $19 million Bugatti La Voiture Noir, these cars are one-offs. But the La Voiture Noir is almost destined to endure a solemn existence, probably hidden for most of its life in a Swiss cave, languishing alongside various other supercars, some valuable art, and the Large Hadron Collider. The homemade cars of the Soviet Era were built to be driven, and driven often. (That’s primarily because those who built them had nothing else to drive.)”

Lanin further tells the story of a collector of these extremely limited-edition DIY vehicles, referred to only as Yura. Yura once displayed his own ingenuity when called upon to transport a new acquisition — a meticulously designed, but long mothballed, racing-style car its builder dubbed the Virus — from Volgograd to his home in St. Petersburg, a nearly 1700 km trip. Yura hitched the Virus to the back of another of his collector’s items, a sleek yellow car he called the LamborZhiga. With a minor jackknife on the way, Yura got his cars home — and remains one of the few deep appreciators of this lost art of automotive magic out there.

While I’d probably be terrified of driving one of these cars, I can recognize that they filled a need — and also scratched a creative itch. We at DFC are no strangers to building things from the ground up. Even in computing, if there hadn’t been someone to DIY the first iteration of some of our key concepts and products, where would we be now?