As the winter solstice nears and the sun disappears from the sky earlier every day, light sources become even more important to we humans. Exposure to sunlight gives us vitamin D and may have an effect on mood. The current trend of hygge, the Danish concept of embracing winter coziness, is so centred around candlelight that researchers are now warning fans about the dangers of indoor pollution given off by their dozens of tapers.

But there’s one kind of evening light issue that interests the team at DFC the most: that which beams straight into our brains from our screens. Scientists have long known that artificial “blue” light from phone, computer, and tablet screens disrupts sleep. But what they didn’t know was the precise mechanism of how this works — until a new study out of the Salk Institute shed light on it. (Sorry, couldn’t resist!)

It involves melanopsin, a protein that is created by cells in the retina when they are exposed to continuous blue light. This protein suppresses the production of melatonin, the hormone that helps us fall and stay asleep. The effects of melanopsin was believed to be dampened by the presence of proteins called arrestins, that were theorized to kick in after several seconds exposure to the light. But when the researchers experimented on mouse retinal cells, they found that there were two types of arrestins working against each other.

“In mice lacking either version of the arrestin protein (beta arrestin 1 and beta arrestin 2), the melanopsin-producing retinal cells failed to sustain their sensitivity to light under prolonged illumination. The reason, it turns out, is that arrestin helps melanopsin regenerate in the retinal cells.

‘Our study suggests the two arrestins accomplish regeneration of melanopsin in a peculiar way,’ [senior author Prof. Satchin] Panda says. ‘One arrestin does its conventional job of arresting the response, and the other helps the melanopsin protein reload its retinal light-sensing co-factor. When these two steps are done in quick succession, the cell appears to respond continuously to light.’”

Now that they know the method by which the retinal cells react to light, the researchers are looking for ways they can begin to suppress it. This would definitely help folks who stare at the ceiling at 3 AM regretting watching all those YouTube videos hours earlier. And there would be a market for photosensitive people, like migraine sufferers as well. So it seems that for those of us huddled at home this winter, in several sweaters, trying to pass the time with news reading and texting our snowbound loved ones, there might be a light at the end of the tunnel! (Sorry again!)

‘Tis the season for your gift-giving holiday of choice — and boy am I over it already!

For those of you still mired in the depths of gift buying, it’s my duty to warn you away from a tech-based gift that is especially hot right now but has chilling implications for its users. (And it’s not any of that infernal Paw Patrol merch!)

Smartwatches for children have been gaining traction over the past couple years, as ways for parents to keep track of  their kids in a hands-off way, while they play in the park or walk home from school. These smartwatches are basically stripped-down, wearable phones: some have limited calling capabilities, SOS buttons that a kid can punch in case of emergency, and all have GPS tracking through a paired app on the parent’s own smartphone.

their kids in a hands-off way, while they play in the park or walk home from school. These smartwatches are basically stripped-down, wearable phones: some have limited calling capabilities, SOS buttons that a kid can punch in case of emergency, and all have GPS tracking through a paired app on the parent’s own smartphone.

The good news is this is great for reducing helicopter parenting. The bad news is REALLY bad — these watches are incredibly hackable. Information can be intercepted and gleaned in a variety of ways: from remotely initiating an outgoing call, effectively broadcasting the child’s voice and surroundings to a bad actor, to spoofing the watch’s location so the child appears to be in a place they aren’t.

The alarm was raised a year ago by the Norwegian Consumer Council, a watchdog organization, which performed several hacks on four popular watch brands to see how far they’d get. The watches performed miserably enough that Germany, that stalwart defender of personal privacy, banned all children’s smartwatches nationwide. The companies responsible and the industry as a whole made noises about fixing the problems — but an analysis of a new brand of smartwatch has shown that has not happened. Pen Test Partners, a security testing firm out of the UK tested out the Misafes children’s smartwatch, and the Norwegian Consumer Council commented that:

“the MiSafes products appeared to be ‘even more problematic’ than the examples it had flagged [last year].

‘This is another example of unsecure products that should never have reached the market,’ said Gro Mette Moen, the watchdog’s acting director of digital services.

‘Our advice is to refrain from buying these smartwatches until the sellers can prove that their features and security standards are satisfactory.’ […]

The BBC found three listings for the watches on eBay earlier this week but the online marketplace said it had since removed them on the grounds of an existing ban on equipment that could be used to spy on people’s activities without their knowledge.”

But it shouldn’t take the BBC weighing in to let us know this is serious. All I think it takes is common sense — no technology can replace good old-fashioned supervision, combined with the street smarts of a well-trained kid. This season, we need to stick to classic gifts that don’t spy on you. Then, equip our kids with the skills to know their world much better than a plastic watch ever could!

At the DFC homestead, we use well water. This was a significant difference from the city supply we were used to before we moved here and a change that gave us pause initially. Even though I’m a trained chemist, I couldn’t help my citified brain briefly piping up: “But if it came out of the ground, it’s not clean. Where’s the chlorine, where’s the fluoride that I know and love?”

This is, of course, nonsense: a well-placed, carefully maintained well that is up to provincial standards is a perfectly healthy way of getting water. In fact, research is showing that well water may, in some ways, be healthier than municipal water. City water is often sourced from open rivers or lakes and requires major chemical intervention with biocides in order to be made drinkable. In contrast, well water is sourced from aquifers that are deep underground; the water in them has not only been naturally filtered through soil, gravel, and rock but is effectively sealed off from surface contaminants and pathogens.

The Atlantic has excerpted a chapter about this from the new book, Never Home Alone: From Microbes to Millipedes, Camel Crickets, and Honeybees, the Natural History of Where We Live, by biologist and ecologist Rob Dunn. Dunn looks at respiratory illnesses that stem from the presence of the genus Mycobacterium and their biofilms in home water pipes — essentially colonies of bacteria and the “gunk” they produce to prevent themselves from being washed away. Mycobacteria are particularly present in showerheads. Many types are benign, especially if they stay on your skin, and your immune system is operational. But if not, some can get in your lungs and make you sick. Writes Dunn:

“When we examined our data, we found that the concentration of chlorine in the tap water from homes using municipal water in the United States was 15 times higher than that of homes with well water. Mycobacteria were twice as common in municipal water as in well water. In some showerheads from municipal water systems, 90 percent of the bacteria were one or another species of Mycobacterium. In contrast, many of the showerheads from houses with well water had no Mycobacterium. Instead, those biofilms tended to have a high biodiversity of other kinds of bacteria.”

As we were pondering these results, Caitlin Proctor at the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology published a new study very much in line with what we were finding. Proctor and her colleagues compared the biofilms of the hoses that lead into showerheads from 76 homes around the world. They found that samples from cities that did not disinfect their water tended to be thicker (more gunk), but samples from those that did disinfect their water were more likely to be lower in diversity and more dominated by mycobacteria.”

It seems that the inside of our showerheads is beset, like the world outside, bysuperbugs of sorts: bacteria or other critters that get meaner and stronger the more trials we throw their way. Though it might mean trouble for our society at large, it makes me feel better about using our well water personally. I’m reminded that there’s such a thing as too clean — and just because we’re multi-celled, it doesn’t mean we’re in charge!

At DFC, we love elegant design: in systems, hardware, and software. Usually, beautiful design draws attention to itself naturally — and there’s nothing more sublime than being called to admire something worthy of admiration!

But there’s lots of subtle solutions, so simply perfect that they seem to have occurred naturally, that fade into the background of everyday life unfairly. I was reminded of this by a new video (itself beautifully animated!) from the knowledge junkies at Great Big Story. The video tells the tale of Dr. Dave Bradley of IBM, who invented the “three finger salute” of Control Alt Delete way back in 1980.

“Ctrl-Alt-Del” didn’t spring fully formed from the ether: Dr. Dave developed it as a three-key-combo designed to reset a program without power cycling. Also known as turning-it-off-and-on-again, power cycling took forever in computing time (“a minute or two”). But, until Dr. Dave, there was no way to restart a hanging program without dragging the whole system along with it.

Dr. Dave’s innovation put an efficient, seconds-long restart in the hands of his fellow developers, and eventually the average PC user. But what I love most about its design is how difficult he made one particular aspect. In “The History of Ctrl+Alt+Del”, Dr Dave narrates:

One of the things we discussed was putting a reset button on it, but if you put it on the system board there was a chance that you could hit it by mistake and all your data gets lost. So what we did was came up with a three key sequence to reset the computer, and you couldn’t hit by mistake: a single Control key, a single Alt key, and then all the way over at the right hand side a single Delete key.”

Dr. Dave was already revolutionary in giving this power to users. But his designer’s attention to context ensured that every restart initiated by a user would be a conscious one, without sacrificing ease of use. Because of this, I think Ctrl-Alt-Del is right up there with Liquid Paper and Newton’s Cradle as a work-easing solution for the ages. In his honour, I offer a three-finger-salute!

With winter around the corner, I’m looking for ways to keep both myself and my furry companions Jill and Samson active. When the snow flies, there are lots of options for fun in the area — but one I hadn’t considered until I read this National Geographic article was dogsledding!

Turns out, some of today’s most effective sled dogs are not the pure-bred malamutes or Siberian Huskies of yore, but a catch-all category called the Alaskan Husky. Alaskan Huskies are a mix of particular breeds (including Northern-type dogs, pointers, and even greyhounds) selected for speed and pulling strength.

But genetics isn’t everything, writes Jane J. Lee: dogs have to have a healthy, almost indiscriminate appetite, to carry them through gruelling, multiple-hundred-kilometre-long races. They also need tough paws — while booties can be worn, they reduce the dogs’ speed overall.

Check and check, for both Samson and Jill… But my favourite aspect of an excellent sled team is one that is easily mapped onto human work relationships too: teamwork!

“Lead dogs—the ones out in front—help maintain order. They execute a musher’s commands, set the team’s pace, and ensure everyone’s going in the right direction. […]

Backing up lead dogs like Sultana are the swing dogs—positioned right behind the leaders. They help to turn the team left or right. Wheel dogs may be last in line, but they help to steer the sled. The good ones know to go wide on turns to guide thesled around trees and other obstacles […]

The dogs in between the swing and wheel positions are called team dogs; they provide the muscle. Their job is to keep pulling until it’s time to stop.”

I wonder if I can convince Jill and Samson to team up and mush me to the grocery store or music practice this winter…? If I can’t get them off the couch, at least I now have concrete knowledge behind a new metaphor for the magic — and necessity — of teamwork

We at DFC are fascinated by possibilities in communication. We love stories about how humans make themselves understood, so we can learn more about how our services can respond. But we also enjoy hearing about animal communication styles — mostly because animals are awesome!

There is extra fascinating — and extra unfortunate — news about human/animal communication from a new study pub lished in Biology Letters. A team from the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science has discovered that wild bottlenose dolphins have been simplifying their language when calling to each other… In order to be heard over the noise of human activity in the oceans.

lished in Biology Letters. A team from the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science has discovered that wild bottlenose dolphins have been simplifying their language when calling to each other… In order to be heard over the noise of human activity in the oceans.

Bottlenose dolphins are notoriously chatty and use their clicks and whistles to maintain group cohesion and announce individual status. There is even evidence that they have names and will call out to each other using them. So, in all kinds of ways, vocalizations are critical to dolphin wellbeing.

The team analyzed 200 underwater recordings of dolphin calls, collected over three months in the North Atlantic. They found that in busy areas, with lots of loud shipping or mining activity, the dolphins simplified and raised the pitch of their communications.

“‘It’s kind of like trying to answer a question in a noisy bar and after repeated attempts to be heard, you just give the shortest answer possible,’ [paper co-author Helen] Bailey said. ‘Dolphins simplified their calls to counter the masking effects of vessel noise.’ […]

‘These whistles are really important,’ Bailey said. ‘Nobody wants to live in a noisy neighborhood. If you have these chronic noise levels, what does this mean to the population?’”

We know an awful lot about physical pollution and its effect on the marine environment. But we’re only just starting to learn about noise pollution. If it has such a far-reaching effect on the savvy dolphins, imagine what else could happen to the widely diverse creatures down there. If we’re not careful, humanity’s legacy will be as the annoyingly loud background noise of the sea.

I love anniversaries, especially if they are of happy events. But remembering tragedies on the date they roll back around is just as important, and probably more informative.

Among the big ones this year is the 100th anniversary of the most devastating influenza pandemic our planet has ever experienced. 20 to 100 million people died of the 1918-19 “Spanish” flu worldwide — up to 5% of the population at the time. The scariest aspect of the Spanish flu was that it picked off the young and healthy, rather than the older or immune-compromised we usually consider prime targets. Some researchers theorize that the flu’s devastation even affected the endgame of World War I.

Science Daily has the breakdown of scientists’ attempts to learn the lessons of the Spanish flu, and apply them to the next pandemic that will come our way. A lot has changed, both in our environment and in our physical selves :

“The authors identify public health as another important factor. In 1918, people suffering from malnutrition and underlying diseases, such as tuberculosis, were more likely to die from the infection. This is still relevant today: climate change could result in crop losses and malnutrition, while increasing antibiotic resistance could see bacterial infections becoming more prevalent. Future pandemics will also face the challenge of obesity, which increases the risk of dying from influenza.”

There is a straightforward way of taking responsibility for our own immune systems though: by getting vaccinated for flu. (Of course, if you are medically cleared for it; i.e. you’ve never had Guillain-Barré, or you’re not allergic to any of the vaccine’s components.) While lots of people have strong opinions about not getting a flu shot, there is strong evidence that it will reduce your chances of catching the flu (or its severity if you do). That’s not only better for your health, but for that of the more vulnerable children and elderly folks around you.

We’re social creatures — we make art, fight wars, and get sick alongside each other. While that makes it easier for a virus to run through us, it’s also our strength in combating it. Good luck this centenary flu season, and here’s hoping we’ll be ready for the next big one!

From exploring pyramids to delivering your new charger cable, drones are increasingly weaving themselves into the fabric of our day-to-day. But in addition to making our lives easier, drones have started saving our lives too.

We wrote about the drone that saved two swimmers on its first day on the job with the lifeguards of Lennox Beach in NSW, Australia. Now, a new research project is running trials of drones with sensors for volatile gases. Effectively, the four-drone team — known collectively as ASTRO — could act as first responders to gas leaks, explosions, or fires, and could determine how safe it is for humans to enter and help.

Conceived by a team of researchers from Baylor and Rice Universities, the drones have faced several challenges in getting up and running. They first needed to be equipped with sensors that weighed less than 1.5 kilos, to make flying possible. Then the fleet required training; first, with a wireless device, they learned to chase automatically, then by “search[ing] and learn[ing]” to create a map of the area they can all follow.

The training all comes together in the ominous-sounding “swarm and track” phase. This is when the drones zero in on their target — in the real world, the presence of a harmful gas.

“‘They determine that this is what we should be measuring, so let’s go collect some high-resolution data,” says [project engineer Edward] Knightly.

‘Of course, gases all have their own spectral signatures,’ he adds. ‘When the drones go out, there’s going to be a mix of different gases. It’s not going to be a clear signal of just one. So we need the drones to learn about the environment, compare it to statistical baseline models we’ve developed, and then be able to identify the sources of hazardous emissions and the boundaries of where they’ve spread.’”

Plans are in the offing to expand the fleet to ten drones soon. In addition to industrial and rescue applications, the creators have also created a mobile app for private users. When rolled out, you could then use your phone to access real-time information about local pollution levels. It looks like ASTRO is the perfect drone storm: lifesaving tech and convenience!

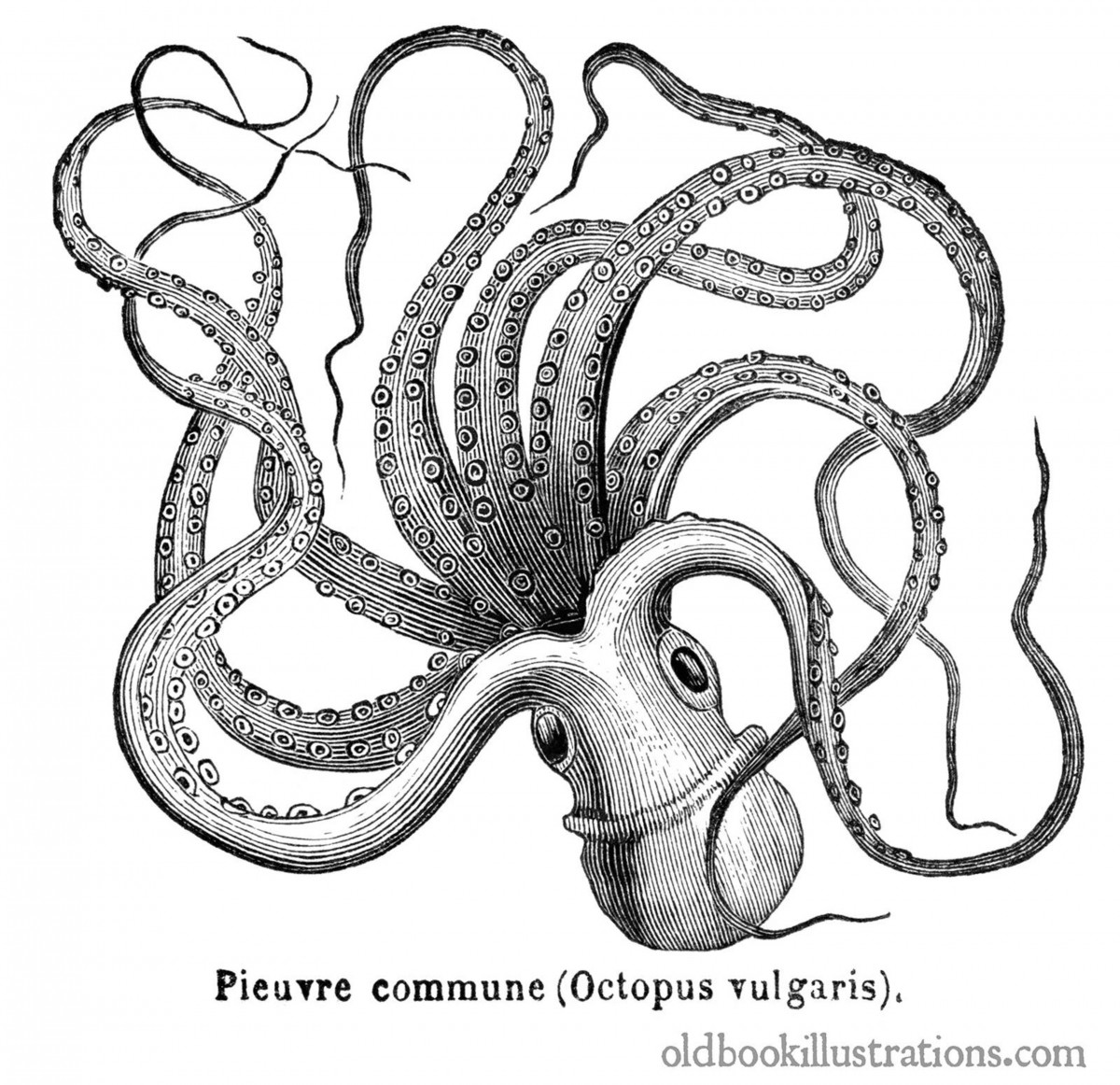

Now, I respect the octopus. It can fit through any hole that is large enough to admit its beak. It’s intelligent enough to know when it’s in trouble and escape. Two-thirds of its total neurons are IN ITS ARMS. And now, thanks to researchers affiliated with Johns Hopkins University, word has come through that the humble Octopus bimaculoides knows how to party.

Specifically, in an experiment, seven representatives of the famously loner species were made more social by exposure to MDMA (the recreational drug that the kids these days are calling “molly”.) This experiment has shown that the system governing human social behaviour — that which controls the serotonin molecule — works similarly in the octopus, despite the massive differences in how our nervous systems are constructed.

The cephalopod subjects exhibited similar behaviours to club kids having a great night out.

“After hanging out in a bath containing ecstasy, the animals moved to a chamber with three rooms to pick from: a central room, one containing a male octopus and another containing a toy. This is a setup frequently used in mice studies. Before MDMA, the octopuses avoided the male octopus. But after the MDMA bath, they spent more time with the other octopus, according to the study published in Current Biology. They also touched the other octopus in what seemed to be an exploratory, rather than aggressive, manner.”

Further study is needed: in particular, the researchers would like to expand the sample size, and see what happens if they block the serotonin transmitter before administering the MDMA. But until then, this research showcases the staggering fact that humans and octopuses, despite 500 million years of divergent evolution, have a deep-set commonality. All this proves to me that octopuses (link: http://grammarist.com/usage/octopi-octopuses/) are the next in line for alpha species!

This month, as I work at my desk, I get to watch the leaves on the birch and maple trees outside my window change from healthy greens to gloriously rich yellows and reds. Fall shows us the flip side of photosynthesis — the process by which deciduous trees produce fabulous amounts of energy in their chlorophyll-rich leaves by converting spring and summer sunlight, CO2, and water into delicious glucose. In the fall, waning sun and colder temperatures cause the trees to reabsorb the chlorophyll and pull nutrients down into their roots for storage till spring. This reveals the beautiful yellows that were there the entire time, just waiting for their moment! (Reds are actually anthocyanins, found in “superfoods” like blueberries, and produced by the trees as a last-gasp sunscreen to protect leaves that are slower to withdraw their nutrients.)

Scientists have tried to replicate Mother Nature’s powerhouse for a long time. If humans could replicate photosynthesis, it would mean renewable, green (pun intended) energy based on one of the most efficient models out there. A new study led by Cambridge University has just shown a more efficient and cheaper way to do exactly that, paving the way for mass use of our “nutrient,” hydrogen.

The process uses hydrogenase, an enzyme present in green algae that acts on water. The enzyme frees the hydrogen in water from its molecular bond with oxygen and allows it to be harvested. In nature, this process was deactivated in plants in evolutionary favour of traditional photosynthesis, which was more important for their survival. The Cambridge scientists have now mimicked this parallel photosynthesis with hydrogenase, for ours.

“But according to [chemist and study lead author Katarzyna] Sokół, most earlier technologies simply won’t scale up to industrial levels, either because they’re too expensive, inefficient, or use materials that pose their own risks as pollutants.

Her team’s approach was to create an electrochemical cell — not unlike a battery — based on the light-collecting biochemistry of a process called photosystem II.

This provided the necessary voltage required for the hydrogenase enzyme to do its work, reducing the hydrogen in water so it can divorce from oxygen and bubble away as a gas.”

There is still lots more research to be done, says the team, before this can be rolled out to the mass market, but its compactness and efficiency both bode well. I love looking to nature for solutions to human problems. Not only are chances good that nature’s already figured it out, but it serves as a reminder that we are part of nature too.